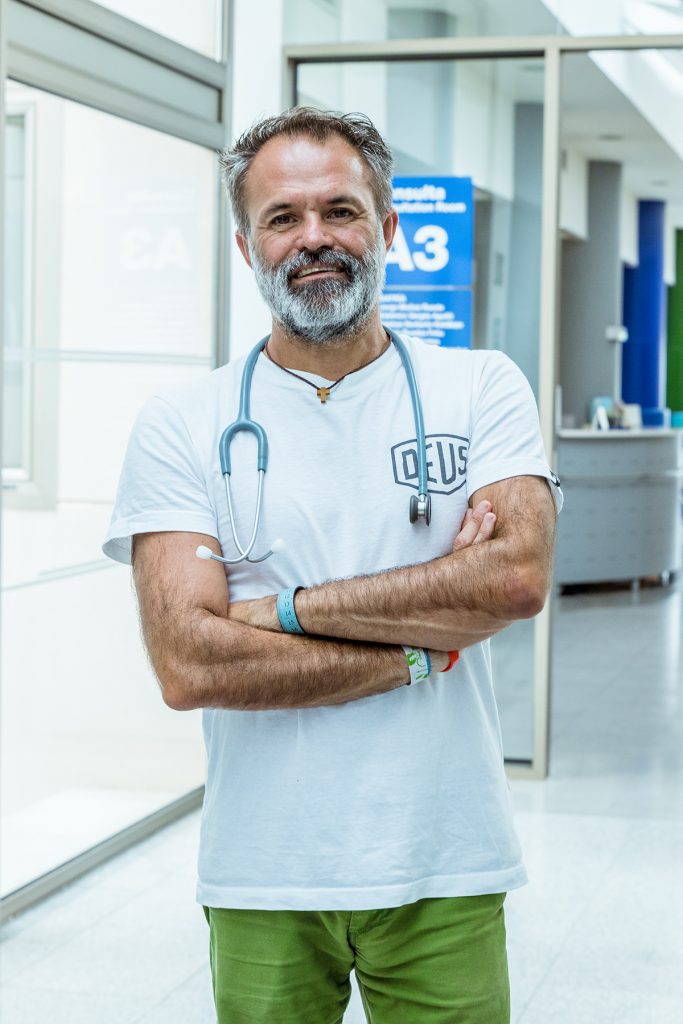

His current practice is far from Africa. He’s head of Paediatrics at Hospital Quironsalud just outside Palma and his agenda is jam-packed. He sees up to seventy children a day. His walls are plastered with colourful testimonials from his little patients who think he’s ‘The Best Doctor in the World’. On the bookshelves are photographs capturing moments of triumph: a young judo player defeating his opponent, a gymnast striking a defiant pose. They are past patients who have overcome adversity and gone on to strive.

His current practice is far from Africa. He’s head of Paediatrics at Hospital Quironsalud just outside Palma and his agenda is jam-packed. He sees up to seventy children a day. His walls are plastered with colourful testimonials from his little patients who think he’s ‘The Best Doctor in the World’. On the bookshelves are photographs capturing moments of triumph: a young judo player defeating his opponent, a gymnast striking a defiant pose. They are past patients who have overcome adversity and gone on to strive.

Connecting with children comes naturally to him. “It’s all about the feeling,” he says, “it’s not something you can learn at university.” He has four children of his own and enjoys a great relationship with them. “I never shout, so when they have a problem, they aren’t scared to come to me.” He is open and direct; no topic is taboo.

He’s not afraid to speak his mind to difficult teenagers who come to the clinic either. “I’ve seen many of them since they were little and I tell them what I think of their behaviour,” he says, “I think their parents asks themselves, why didn’t I tell them that? I’ve got good communication skills and I take advantage of them.”

Working as a paediatrician in Palma is a very different experience to that of working in Chad. Dr Muñoz’s first visit to what he calls the ‘dry heart of Africa’ was in 2012. Magdalena Ribas, a nurse and Combonian missionary nun, was visiting her native home of Mallorca on a rare holiday and told him about her work at St Joseph de Bebedjia in Chad where she had been living for thirty years. She was looking for funding but Muñoz decided it would be easier if he went himself, along with his colleague Dr Reina Lladó.

“It was shocking,” he says. Before he’d even unpacked his bag after a 600km drive through difficult terrain, he lost his first patient. “We were losing three children a day. We weren’t used to it.”

On his return he set up the charity ‘Ayuda Al Chad’ (Help Chad) to raise awareness and funds. The following year he went back, and this time he channelled his anger and his sadness into an online diary which made the front pages of ‘El Mundo’.

On his third trip he was accompanied by the brilliant photographer and filmmaker, Pep Bonet, whom Muñoz describes as ‘a genius.’ The resulting documentary shares the name of the doctor’s book: The Most Beautiful Hell I Know. The beauty doesn’t come from African sunsets but from the gratitude and generosity of these children who have nothing.

On his third trip he was accompanied by the brilliant photographer and filmmaker, Pep Bonet, whom Muñoz describes as ‘a genius.’ The resulting documentary shares the name of the doctor’s book: The Most Beautiful Hell I Know. The beauty doesn’t come from African sunsets but from the gratitude and generosity of these children who have nothing.

I ask him how he coped returning to a world of ego and excesses and he describes how his mind is made up of little rooms. He is able to shut off one door to the suffering in Chad and be fully present in whichever ‘room’ he needs to be. But he admits the first week after coming back always goes by in a blur. “My mind is shaken,” he says, “it’s so horrific and I need time to settle.”

Ever since going to Chad he finds himself living every day as if it were his last and wondering how he can be a better person. Sport, running in particular, is one way he de-stresses. It’s also when the ideas come. Not content to be ‘The Best Doctor in the World’ to Mallorca’s children, he’s also always on the look-out for opportunities to raise funds for the charity. He mentions a children’s fashion range he’s working on but isn’t ready to tell me more just yet.

An inspirational man without doubt, and also one who believes everyone has the potential for greatness. “You don’t know how strong you are until being strong is the only option,” he writes. Hopefully we won’t be put to such a tough test to realise whoever we are, wherever we are, we can make this world a more compassionate place.

Photos by Estefanía Duran & Pep Bonet